The west’s leading economic thinktank has predicted a tentative recovery for the global economy this year and next but warned of risks from fragile trust in government, weak wage growth and persistent inequality.

In its latest health check on growth prospects, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development described the outlook for the global economy almost a decade on from the financial crash as “better, but not good enough”.

The Paris-based organisation nudged up its forecasts for global growth this year. But it trimmed its outlook for the US, to show growth accelerating a little more gently than in its previous assessment made in March.

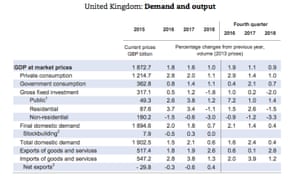

It made no changes to predictions that the UK will suffer a Brexit-related slowdown, with growth easing from 1.8% in 2016 to 1.6% this year and just 1% in 2018.

After 3% growth in 2016, the global economy is now expected to expand 3.5% this year and 3.6% in 2018. That compares with previous forecasts for 3.3% and 3.6%, respectively.

“After many years of weak recovery, with global growth in 2016 at the lowest rate since 2009, some signs of improvement have begun to appear,” OECD’s chief economist, Catherine Mann, wrote in the new outlook.

“Trade and manufacturing output growth have picked up from a very low level, helped by firmer domestic demand growth in Asia and Europe, and private sector confidence has strengthened. But policy uncertainty remains high, trust in government has diminished, wage growth is still weak, inequality persists, and imbalances and vulnerabilities remain in financial markets.”

Mann warned that despite a more buoyant mood in the global economy, policymakers could not afford to be complacent. The recovery was not yet strong enough to sustainably improve people’s wellbeing or to reduce persistent inequalities, she said.

The OECD devoted a significant proportion of its latest report to the possible forces behind a backlash against globalisation. That discontent was seen as a key factor behind Donald Trump’s victory in the race for the US presidency, since when he has pledged to put “America first”. Anti-globalisation sentiment also appears to have boosted protectionist politicians in other countries, including France where the far-right candidate Marine Le Pen made it to the final round of the presidential election but lost to the centrist Emmanuel Macron.

The OECD said international trade had been a “powerful engine of global economic growth and convergence in living standards between countries” but that despite those gains, the backlash against it had been rising.

It cited multiple reasons for popular dissatisfaction, including the rise in inequality in many countries since the early 2000s that meant many households had had little or no gain in disposable income. The decline of middle-skilled jobs was another factor, as was the drop in manufacturing employment that had continued in almost all of the 35 OECD countries.

The report also highlighted that while employment growth had recovered relatively well in recent years, in some ways the quality of work was more precarious.

Its outlook for the US noted that risks remained “sizeable”. Primary among those was uncertainty around the size and timing of any boost from tax and spending policy. There was also a risk that the labour market could tighten more quickly than projected, stoking wage pressures and meaning the US Federal Reserve increases interest rates more rapidly than expected.

The US economy is predicted to grow 2.1% this year and 2.4% in 2018, down from March’s forecasts for 2.4% and 2.8%, respectively.

The eurozone forecasts were nudged up to 1.8% growth this year and next, from 1.6% for both years predicted in March.

The OECD highlighted risks stemming from financial markets where share prices in the US, UK and elsewhere have hit record highs, seemingly out of sync with prospects for the real economy.

There were further warnings about high house prices in some countries and about the consequences of years or record low interest rates following the global financial crisis. That “over-reliance” on very loose monetary policy had led to vulnerabilities associated with rising debt levels, elevated asset prices and investors searching for ways to get a yield on their investments.

The OECD noted that the UK, Canada, Sweden, Australia and other countries had experienced rapid house price growth.

“As past experience has shown, rapid house price gains can be a precursor of an economic downturn, especially when they occur simultaneously in a large number of economies,” it said.

Following June’s referendum result, the OECD was, like many forecasters, forced to backtrack on its earlier warning that the UK would suffer instant damage from the Brexit vote. Its latest outlook noted there was support for UK growth from low interest rates and from planned spending cuts being pushed back.

But echoing recent signs that consumers have become more cautious, the group said the pound’s sharp drop since the Brexit vote last June had pushed up inflation, denting household income growth and household spending. It also warned business investment would decline sharply, amid continuing uncertainty about the future relationship between the UK and the EU and lower corporate profit margins.